When I started following the Red Sox, they were terrible. They rarely won. We didn’t care. We wanted to be at Fenway Park. We loved the way it smelled, the way the hot dogs tasted, and even the stickiness on the floor when we walked the aisles to find seats. We picked up score cards on our way into the park and marched through the turnstiles. We talked to the ticket-takers, who seemed ancient to us back then. They were probably in their forties. Ancient, indeed.

Box seats cost $3; unassigned bleacher seats were $1. And the bargain of the century for those of us who were under 18 were right-field grandstand tickets for seventy-five cents. The Red Sox did their best to fill the seats, when most of the games took place during the day, because most fans were at work. Those of us who could to the game had very little income, so seventy-five cents was the going rate.

We made friends with the ushers, who often would let us leave the bleachers or right-field seats to sit in empty box seats after the seventh-inning stretch. We even had the opportunity to sit right behind home plate and watch the pitchers throw directly into the catcher’s mitt. We were safe under the netting as foul balls flew and batters cursed bad calls from the umpires.

We were in what today would be called the expensive seats, the ones reserved for celebrities and scouts with the radar guns you might see on TV. Back then, no seats existed atop Fenway’s famous Green Monster; the only thing the Monster held was Fenway’s mechanical scoreboard. The electronic scoreboard would be years in the future for fabulous Fenway. In fact, we didn’t even know what fancy electronics were back then, in the days before computers and cell phones.

Fenway Park was not the place to be, as it is today. Business people didn’t bring their clients to Fenway to impress them. It was just a ballpark with a last-place team that hadn’t won a World Series since 1918. Yes, they were Major League ballplayers, who’d worked their way up through the minors, but since Ted Williams retired, they hadn’t done much.

Until 1967.

The Impossible Dream Team.

The Red Sox hired Dick Williams to manage the team in 1967. He imposed strict discipline on the team during spring training, and he carried that throughout the year. The players rebelled until they saw results during the regular season.

They had the talent; in 1967, they finally had the manager who wouldn’t take any guff and who had the vision to lead them to the World Series.

For those of us who had supported them for years of empty ballparks, when organist Richard Kiley played the organ and the notes echoed off the vacant seats as if he were serenading the Grand Canyon, this was nothing short of a miracle. As the team won more and more games, the stands began to fill up with fans who hadn’t had time for baseball for years.

We couldn’t get tickets.

Our friends the ushers couldn’t let use migrate into the box seats anymore—because they had people in them.

We thought, “Hey! Wait a minute! Where did these fair-weather fans come from? We’re the ones who supported these guys when they weren’t winning! Why can’t we get near the ballpark?”

As difficult as it was for us to realize, we weren’t the only people who loved the Red Sox. To be sure, we’d been the ones who’d come out for baseball even when the team had been lucky to get three or four thousand people in the park, but in 1967, people finally weren’t ashamed to admit they were Red Sox fans.

Before 1967, people may have listened on the radio, only to complain to the voice of Ned Martin or Curt Gowdy that the Sox were bums. They’d groan when Mel Parnell said dumb things such as, “As you know, fans, this is the first game of a doubleheader. And the second game will follow the first.”

But when the team was winning, those same complainers all of a sudden were the biggest supporters. They’d traded their protesting for praising, couldn’t find anything to whine about, and, by golly, put their fannies in the seats at Fenway Park.

The ushers, sporting uniforms that looked more like doormen at fancy New York City apartment buildings, beamed as they wiped off box seats from the previous evening’s moisture and received hefty tips from happy fans they’d guided.

During the Impossible Dream season, those of us of who’d been with the team for many years, who hadn’t been able to afford tips and barely had enough money to buy tickets, discovered that some of those same ushers who’d flashed a smile and welcomed us to Fenway day after day soon forgot who we were. If anything, we found ourselves relegated to the highest row of the bleachers or the right-field grandstand—if we could get into the park at all.

Some of us discovered that it was better to stay home and listen to ballgames on the radio. The team was even good enough to be broadcast on national tv as well.

That fall, I headed off to the University of Tennessee to study journalism.

Wouldn’t you know it—they made it to the World Series?

Wouldn’t you know they’d play one of the most historic World Series of all?

The 1967 World Series between the Red Sox and St. Louis Cardinals saw some of the most incredible pitching, including match-ups between Hall-of-Famer Bob Gibson and Red Sox ace Jim Lonborg.

The ’67 series went seven games. The Red Sox and Cards played their hearts out. I watched on a tv in the Sophronia Strong dormitory in Knoxville, Tennessee, the only Red Sox fan surrounded by many Cardinal fans. Tim McCarver, long-time baseball broadcaster (who often showed his disdain for the Red Sox when he worked for the networks), was Gibson’s catcher. The drama between the two teams was the very essence of what baseball means to me.

Lonborg’s earned run average was less than two during the series; Gibson’s was better. I hung on every pitch, every crack of the bat, every ground ball, every line drive.

When the last out was made and the Red Sox lost in seven, I was heartbroken. I was not quite 19 years old (my birthday was the following month).

Only in retrospect can I admit that this was one of the finest displays of baseball in my lifetime, that Bob Gibson outdueled my team’s ace, that the Cardinals were just a tiny bit better than my team was, and yet, it was baseball at its ultimate—the very definition of why I love the game. Strategy. Teamwork. Heart and soul. Blood, sweat and tears.

St. Louis had the champagne that year. It could have gone the other way—that’s how close it was. That’s how a champion should be determined.

How fortunate was I, then, to have seen that 1967 World Series, the Impossible Dream team, to watch what had only one year before been a last-place, floundering group of undisciplined men, come together and re-group into champions? How fortunate was I, then, to have been a fan all along, when they were terrible, and to realize that loyalty pays off, that my love of baseball and team--this team—in my heart was the right thing?

At the age of almost 19, I was so tenuous in my decisions, and spent many sleepless nights wondering if I’d made the right choices about so many things. Not once did I ever feel as if I’d chosen the wrong baseball team to love.

Tested often, yes; wrong, no. Second-guessing the management, yes; wrong choice, no.

No matter where I am, whether it was Knoxville in 1967 or Schenectady now, as the old song says, “I love that dirty water…oh, Boston, you’re my home…”

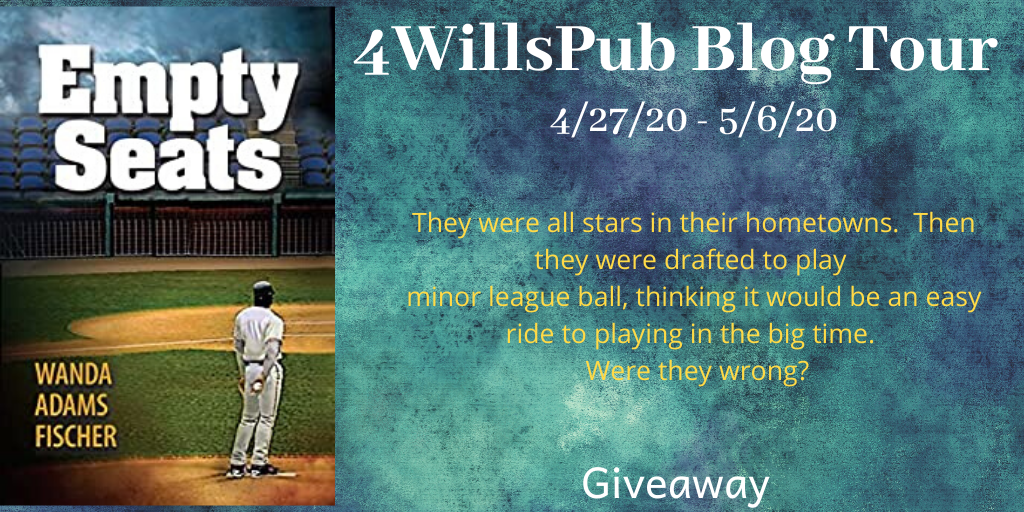

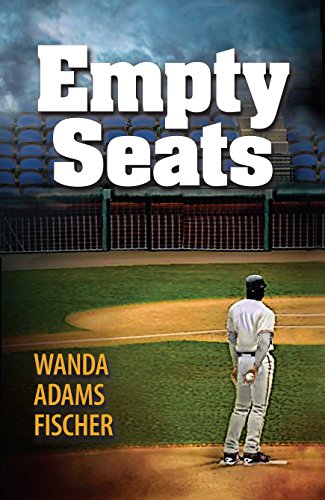

What Little Leaguer doesn’t dream of walking from the dugout onto a Major League baseball field, facing his long-time idol and striking his out? Empty Seats follows three different minor-league baseball pitchers as they follow their dreams to climb the ladder from minor- to major-league ball, while facing challenges along the way—not always on the baseball diamond. This coming-of-age novel takes on success and failure in unexpected ways. One reviewer calls this book “a tragic version of ‘The Sandlot.’”

(Winner of the 2019 New Apple Award and 2019 Independent Publishing Award)

Following a successful 40-year career in public relations/marketing/media relations, Wanda Adams Fischer parlayed her love for baseball into her first novel, Empty Seats. She began writing poetry and short stories when she was in the second grade in her hometown of Weymouth, Massachusetts and has continued to write for more than six decades. In addition to her “day” job, she has been a folk music DJ on public radio for more than 40 years, including more than 37 at WAMC-FM, the Albany, New York-based National Public Radio affiliate. In 2019, Folk Alliance International inducted her into their Folk D-J Hall of Fame. A singer/songwriter in her own right, she’s produced one CD, “Singing Along with the Radio.” She’s also a competitive tennis player and has captained several United States Tennis Association senior teams that have secured berths at sectional and national events. She earned a bachelor’s degree in English from Northeastern University in Boston. She lives in Schenectady, NY, with her husband of 47 years, Bill, a retired family physician, whom she met at a coffeehouse in Boston in 1966; they have two grown children and six grandchildren.

@emptyseatsnovel

https://www.facebook.com/EmptySeatsNovel/

https://www.wandafischer.com

Amazon and Other Purchase Links

Book: http://amzn.to/2KzWPQf

Audio book: http://bit.ly/2TKo3UC

https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/empty-seats-wanda-adams-fischer/1127282887?ean=9780999504901

http://wandafischer.com/buy-my-book/